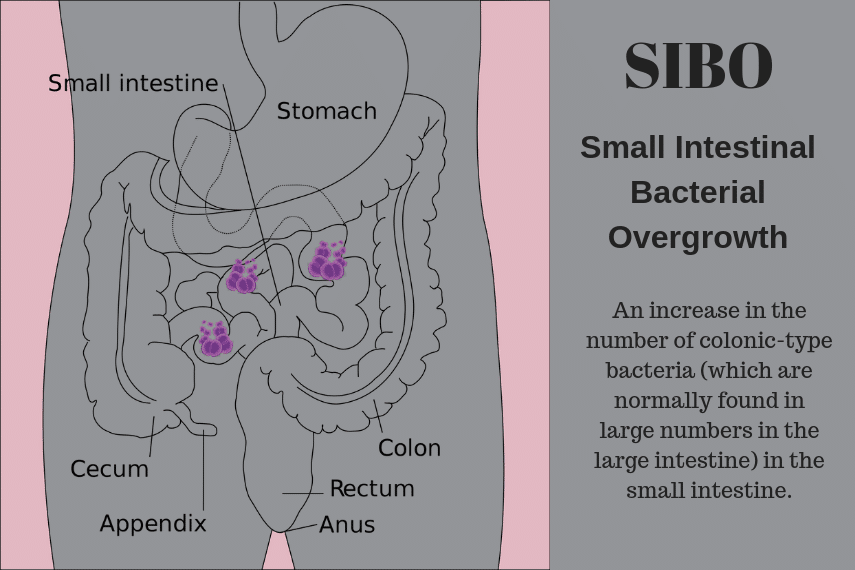

What is SIBO?

Simply stated, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is an increase in the number of colonic-type bacteria (which are normally found in large numbers in the large intestine) in the small intestine.

The presence of bacteria in our gastro-intestinal (GI) tract is normal and helpful. In fact, it’s estimated that there are 10 times as many bacterial cells in the human body as there are human cells!

Our gut bacteria provide support for digestion; produce short chain fatty acids that are important for immune health, metabolism and disease prevention; help fight off the growth of “bad bacteria” (pathogens), and even produce a number of important vitamins.

The problem comes, however, when large numbers of bacteria from the large intestine migrate to the small intestine, and/or too many of the “wrong” types of bacteria migrate northward.

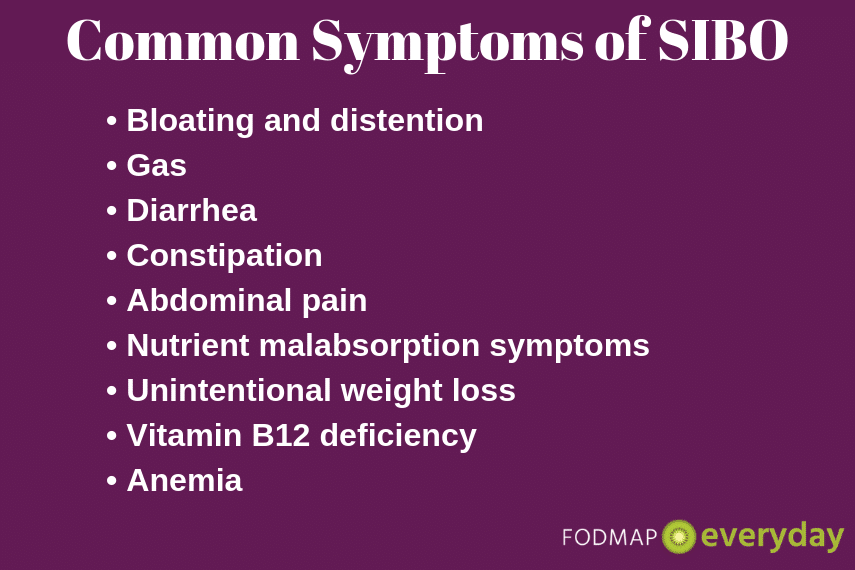

These bacteria then wreak havoc on our digestion and can lead to uncomfortable symptoms such as bloating, gas and belching, diarrhea, weight loss, constipation and/or abdominal pain.

These symptoms, unfortunately, are quite vague and mirror a number of other GI disorders, so it can be frustrating or confusing for individuals to figure out what is really going on.

The American College of Gastroenterology defines SIBO as an excessive microbial burden that resides in the small intestine. For that microbial burden to be classified as SIBO, it must be both measurable and associated with gastrointestinal symptoms. So, we can think of SIBO as a big bacterial party that spilled over from the colon (where it’s supposed to be) to the small bowel (where it’s not supposed to be).

There is a lot of pseudo-science on the Internet about SIBO. Thus, the rest of this article will focus on providing science-based information regarding how SIBO is diagnosed, who may be at risk for it, and how it’s typically treated.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

The gold standard for the diagnosis of SIBO is jejeunal aspiration – taking a sample of liquid from the small intestine in order to identify and quantify the bacteria present there. This method is invasive and quite costly, so it is not often used.

Other, more commonly used methods include a complete assessment of GI symptoms and other health related indicators and/or hydrogen breath testing, such as glucose or lactulose testing [1].

Current Tests for SIBO Include:

- Hydrogen breath tests

- Methane breath rests.

- Hydrogen sulfide test (under development)

During hydrogen breath testing, an individual consumes a drink that contains a specific amount of sugar (either glucose or lactulose) and then blows into a bag or tube to provide a breath sample several times over the course of two to three hours.

The premise is that if your small intestine has a large number of bacteria present that ferment unabsorbed sugars (which produce hydrogen gas – e.g. your bloating and belching symptoms), your body will try to expel this gas in a variety of ways, including breathing out.

The type(s) of gas present in a positive breath test is indicative of the type of overgrown bacteria in the small bowel, as well as the associated gastrointestinal symptoms and potential treatment methods.

Different Types of SIBO – and IMO (Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth)

There are actually a few different types of SIBO, which we outline below. Please make note of the newly termed IMO (intestinal methanogen overgrowth) mentioned in the first bullet point:

- Constipation-predominant “SIBO” is associated with elevated levels of methane gas in breath tests and a microbe in stool called M. smithii. Now, I put “SIBO” in quotes here for an important reason: the microbe associated with methane-dominant/constipation-predominant “SIBO” (M.smithii) is actually not bacteria at all. It’s something called a methanogen, which falls under the archaea kingdom. The more methanogenic flora in stool, the greater the presence of chronic constipation, likely due to slowed intestinal transit. According to the latest clinical guideline from the American College of Gastroenterology, a positive methane breath test is actually no longer considered indicative of SIBO, because it is not caused by bacteria. Instead, it’s called intestinal methanogen overgrowth (or IMO).

- Hydrogen-dominant SIBO, on the other hand, is most associated with symptoms of diarrhea, loose stools, cramping and abdominal pain. This hydrogen is produced in the small intestine during fermentation of ingested carbohydrates, when that fermentation should be happening in the colon. Interestingly, hydrogen is also a fuel source for methanogens, which the literature suggests can be responsible for slowed motility and constipation. The more you feed the methanogens with excessive hydrogen, the more methane will be produced. The more methane is produced, the more bloating and constipation will occur. This is one of the reasons why we can’t ascribe a one-to-one correlation between specific symptoms and SIBO types – there is always some overlap!

- Lastly, hydrogen-sulfide-dominant SIBO is most associated with excessive belching, nausea, foul odorous gas (rotten egg, sulfuric smell), alternating constipation/diarrhea, and even increased histamine sensitivity. Like methanogens, the type of microbes that are associated with hydrogen-sulfide SIBO use hydrogen as a fuel source. This is the least well-understood SIBO form, namely because a commercial testing system that includes hydrogen-sulfide is not yet available and a cutoff value for diagnosis of SIBO using H2S gas remains to be validated.

While breath testing is relatively straight-forward, affordable, and non-invasive for the identification of SIBO or IMO, it’s also worth noting that these tests are far from perfect. A good diagnostic tool is one that successfully identifies true positives (sensitivity) and true negatives (specificity) at least 90% of the time.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies showed that the lactulose breath test and glucose breath test had a pooled sensitivity of only 42.0% and 54.5%, and a pooled specificity 70.6% and 83.2%, respectively. For this reason, there is still quite of bit of discord around the usefulness of breath testing for the purpose of SIBO and IMO diagnosis, though for now it is considered the most practical option.

Not All Tests or Labs Are Alike

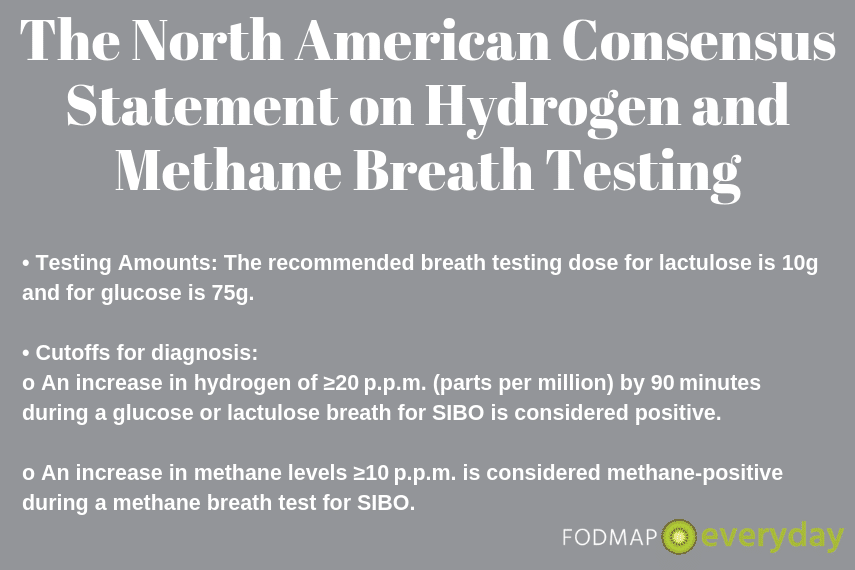

Historically, there has not been a consistent global testing process nor unified diagnostic cutoff points to diagnose SIBO. This means that different testing centers may use different sugars, different doses of sugar, different testing methods, and/or different increases in breath hydrogen to provide a diagnosis.

Even the current gold standard diagnostic tool (small bowel aspirate) is far from perfect, due to the fact the results of the test will vary depending on which part of the small bowel is sampled.

Or, put more simply, you could get a positive test for SIBO at one testing location and a negative test at a different one. Not very helpful!

In addition, some individuals produce hydrogen gas in response to bacterial fermentation, while others tend to produce methane gas. Thus, the commonly used hydrogen breath tests are neither appropriate nor useful for those methane-producing individuals.

It’s therefore recommended that patients test for both hydrogen and methane production, but this doesn’t always happen.

Also, in addition, there is new research that indicates that some individuals may produce significant amounts of hydrogen sulfide gas, rather than hydrogen or methane, but there is not yet a standardized, widely available test for this (however it is under development and you can read about it here and here [5, 6]).

So the choice of test and testing procedure has been widely variable to date.

What Can Lead To A “False Positive” SIBO Test?

There are also other disorders of the GI tract where carbohydrate malabsorption (and thus, hydrogen production) can occur, such as celiac disease or chronic pancreatitis, potentially leading to a false positive SIBO test.

Delayed gastric emptying (when your food stays longer in the stomach and small intestine, giving bacteria more time to ferment unabsorbed sugars) can also lead to a false positive test.

Finally, an accurate breath test also requires that the patient follow a number of specific dietary and lifestyle restrictions prior to the test. If these are not carefully followed, the test may be inaccurate.

Global Consensus About Testing Methods

Recently, there has been more global discussion to strive for consensus in this area. In May 2017, a group of GI experts released the North American Consensus Statement on hydrogen- and methane-based breath testing, which included recommended doses of lactulose, glucose, fructose and lactose for breath testing (some of which are used for other diagnoses besides SIBO) and minimum cutoff points [7].

Additionally, similar guidelines were issued in 2009 by the Italian H2-breath Testing Consensus Conference Working Group and in in 2005 by the German Society of Neurogastromotility.

These new guidelines will hopefully serve to standardize the preparation and interpretation of these breath tests, but it is still somewhat early and a great deal of variability in testing procedures remains.

Who Is at Risk for SIBO or IMO?

Who Is at Risk for SIBO or IMO?

The overall pathophysiology behind SIBO is complex: i.e. it’s not entirely clear why SIBO occurs, however there are some previously identified risk factors. Specifically, SIBO may be more common in the following individuals:

- Those who have recently suffered from foodborne illness. These individuals may also develop or post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) separately from or in addition to SIBO.

- Inflammatory bowel disease sufferers[8].

- People with low levels of stomach acid, such as those who take frequent proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs). Stomach acid normally acts as a “gatekeeper” and can prevent against rapid growth of certain types of pathogenic or “bad” bacteria. (Some recent studies have cast some doubt on this, however [9]).

- One meta-analysis of 25 studies and over 6,000 subjects showed that 31% of patients diagnosed with IBS also tested positive for SIBO. Compared to controls, those with IBS were 3.7 times more likely to also test positive SIBO. That same meta-analysis also compared SIBO prevalence in patients with IBS to healthy controls who did not have IBS. Those with IBS were almost 5 times more likely to be diagnosed SIBO than non-IBS healthy controls (OR = 4.9; 95% CI 2.8-8.6). Specifically, diarrhea related to H2 and H2S SIBO is more closely associated with IBS-D, while constipation related to IMO more closely associated with IBS-C.

- Those with gut motility issues, such as gastroparesis, individuals who have had GI surgery or alterations in their GI tract (e.g. bariatric surgery, colectomy or other bowel resections[11]).

- People with a history of alcohol abuse, individuals with alcoholic or idiopathic chronic pancreatitis, immuno-compromised individuals, celiac sufferers and individuals with long-standing diabetes and related renal and GI neuropathy might also be at greater risk [12, 13, 14].

If you fall into any of these categories and are experiencing symptoms of SIBO, please consult with your doctor!

The Importance of Treatment

Untreated, SIBO can affect the function of the digestive system by altering the layer of the gut (mucosa) that is responsible for preventing bad bacteria and undigested foods from inadvertently entering your blood circulation. This can lead to low-grade inflammation and increased risk for other inflammatory issues throughout the body.

There are also potential nutritional consequences of untreated SIBO, such as malabsorption, nutrient deficiencies and weight loss. The presence of excessive bacteria in the small intestine leads to competition for nutritional resources (where both the bacteria and the body are fighting for nourishment), which may create deficiencies in folic acid, iron, and vitamin B12. Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K) may also be deficient in patients with SIBO due to deconjugation of bile acids in the presence of excess bacteria, inhibiting fat absorption.

Finally, individuals who just don’t feel well and experience recurring gut symptoms may alter their diet to address perceived food sensitivities. This can lead to the development of food fears, disordered eating, and/or unintended weight loss, as well as further perturbation of the gut microbiota from widespread food elimination.

Commonly Prescribed Antibiotics

The most commonly prescribed treatment for SIBO is antibiotics such as rifaximin, which is a broad spectrum, minimally absorbed antibiotic. Rifaximin works only in the gut and does not seem to cause major disturbances in overall (healthy) gut bacteria in the long-term [17, 18].

The optimal duration of antibiotic therapy is currently not known, though most studies have used a 7- to 10-day course [19], and thus this is the general recommendation used by many physicians or gastroenterologists.

A combination of rifaximin and neomycin antibiotic therapy may be indicated in those diagnosed with IMO, particularly in patients also diagnosed with IBS-C.

The Role of Probiotics

Probiotics are also often used, either alone or in combination with antibiotics, though the science here is still nascent. (Read about our recommended probiotics).

A small 2014 study showed that individuals with SIBO who received both antibiotics and a lactobacillus containing probiotic showed a better response than those who received antibiotics alone, with the combined treatment completely relieving abdominal pain in 93% of individuals receiving it [20].

Prokinetics, medications that increase gut motility and, are also used in some cases, such as for individuals with gastroparesis as well as SIBO[21].

The Role of Diet

A key misconception with SIBO is that dietary changes or supplements will reverse or cure it. Unfortunately this is not correct. Nutritional interventions for SIBO may help manage or reduce symptoms and can increase the effectiveness or durability of antibiotic treatment, but they cannot treat SIBO in isolation.

In terms of dietary treatment to help manage symptoms, it is theorized that a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates can be utilized, and there are several “versions” of such dietary strategies in use, including the Low FODMAP Diet, Cedars Sinai Low Fermentation Diet, Specific Carbohydrate Diet, Elemental Diet, GAPS or SIBO Bi-phasic Diet. Unfortunately, there is very limited evidence for most of these protocols, with the Low FODMAP Diet having a slight edge in overall research quantity and quality.

Recurring SIBO

In the end, unfortunately, while there are a number of treatment options for SIBO, treatment is not consistently as effective as anyone would like (doctors or patients) and re-treatment is often required. It’s estimated that up to 50% of individuals see a recurrence post-treatment [24].

It’s possible that treating the bacteria rather than the underlying cause is the issue here, however it can be challenging to diagnose and understand the actual cause in some individuals.

This gap in understanding the root causes of SIBO may leave some individuals suffering from symptoms off and on for years. Luckily, scientists are making significant strides in this area, with new studies being conducted regularly.

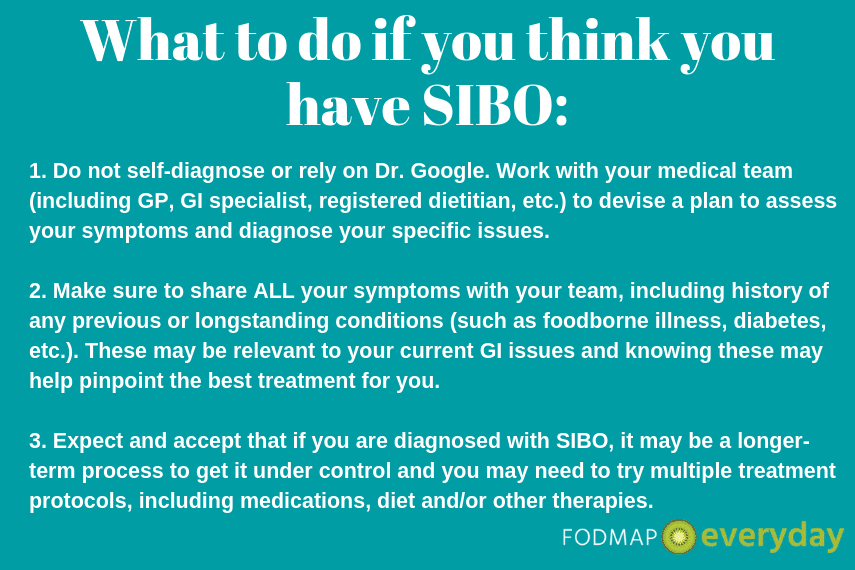

The Takeaway

SIBO is a real issue, especially for individuals who have other gut issues or related illnesses, such as IBS or celiac disease. However, diagnostic and treatment methodologies are still evolving. If you think you may have SIBO, please see the above graphic for tips for approaching this with your medical team. The low FODMAP diet might be recommended in addition to other medical therapies.

You may want to read GERD, IBS & the Low FODMAP Diet

References

1 Simrén, M., & Stotzer, P. (2006). Use and abuse of hydrogen breath tests. Gut, 55(3), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2005.075127

2 Dukowicz, A. C., Lacy, B. E., & Levine, G. M. (2007). Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Comprehensive Review. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 3(2), 112–122

3 J Breath Res. 2016 May 10;10(2):026010. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/2/026010

4 Cedars-Sinai Research Identifies Gut Gas Linked to Diarrhea. (2018). Cedars-Sinai Research Identifies Gut Gas Linked to Diarrhea. [online] Available at: https://www.cedars-sinai.org/newsroom/cedars-sinai-research-identifies-gut-gas-linked-to-diarrhea/ [Accessed 27 Jul. 2018].

5 Simrén, M., & Stotzer, P. (2006). Use and abuse of hydrogen breath tests. Gut, 55(3), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2005.075127

6 Hydrogen Breath Test: Purpose, Preparation, Procedure, and Results. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/hydrogen-breath-test

7 Rezaie, A., Buresi, M., Lembo, A., Lin, H., McCallum, R., Rao, S., … Pimentel, M. (2017). Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 112(5), 775–784. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2017.46

8 Bures, J., Cyrany, J., Kohoutova, D., Förstl, M., Rejchrt, S., Kvetina, J., … Kopacova, M. (2010). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 16(24), 2978–2990. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.2978

9 Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Pyleris E, Barbatzas C, Pistiki A, Pimentel M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated with irritable bowel syndrome and is independent of proton pump inhibitor usage. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:67.

10 Sachdeva, S. , Rawat, A. K., Reddy, R. S. and Puri, A. S. (2011), Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) in irritable bowel syndrome: Frequency and predictors. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 26: 135-138. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06654.x

11 Rao, S., Tan, G., Abdulla, H., Yu, S., Larion, S., & Leelasinjaroen, P. (2018). Does colectomy predispose to small intestinal bacterial (SIBO) and fungal overgrowth (SIFO)?. Clinical And Translational Gastroenterology, 9(4). doi: 10.1038/s41424-018-0011-x

12 Kumar, K., Ghoshal, U., Srivastava, D., Misra, A., & Mohindra, S. (2014). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is common both among patients with alcoholic and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology, 14(4), 280-283. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2014.05.792

13 Hauge, T., Persson, J., & Danielsson, D. (1997). Mucosal Bacterial Growth in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract in Alcoholics (Heavy Drinkers). Digestion, 58(6), 591-595. doi: 10.1159/000201507

14 Bures, J., Cyrany, J., Kohoutova, D., Förstl, M., Rejchrt, S., Kvetina, J., … Kopacova, M. (2010). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 16(24), 2978–2990. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.2978

15 Miazga, A., Osiński, M., Cichy, W., & Żaba, R. (2015). Current views on the etiopathogenesis, clinical manifestation, diagnostics, treatment and correlation with other nosological entities of SIBO. Advances In Medical Sciences, 60(1), 118-124. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2014.09.001

16 Khalighi, A. R., Khalighi, M. R., Behdani, R., Jamali, J., Khosravi, A., Kouhestani, S., … Khalighi, N. (2014). Evaluating the efficacy of probiotic on treatment in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) – A pilot study. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 140(5), 604–608.

17 Bures, J., Cyrany, J., Kohoutova, D., Förstl, M., Rejchrt, S., Kvetina, J., … Kopacova, M. (2010). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 16(24), 2978–2990. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.2978

18 Gupta, K., Ghuman, H., & Handa, S. (2017). Review of Rifaximin: Latest Treatment Frontier for Irritable Bowel Syndrome Mechanism of Action and Clinical Profile. Clinical Medicine Insights: Gastroenterology, 10, 117955221772890. doi: 10.1177/1179552217728905

19 Dukowicz, A. C., Lacy, B. E., & Levine, G. M. (2007). Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Comprehensive Review. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 3(2), 112–122.

20 Khalighi, A. R., Khalighi, M. R., Behdani, R., Jamali, J., Khosravi, A., Kouhestani, S., … Khalighi, N. (2014). Evaluating the efficacy of probiotic on treatment in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) – A pilot study. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 140(5), 604–608.

21 Bures, J., Cyrany, J., Kohoutova, D., Förstl, M., Rejchrt, S., Kvetina, J., … Kopacova, M. (2010). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 16(24), 2978–2990. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.2978

22 What’s the go with SIBO???. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.monashfodmap.com/blog/whats-go-with-sibo/

23 Ghoshal, U. C., Shukla, R., & Ghoshal, U. (2017). Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Bridge between Functional Organic Dichotomy. Gut and Liver, 11(2), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl16126

24 Bures, J., Cyrany, J., Kohoutova, D., Förstl, M., Rejchrt, S., Kvetina, J., … Kopacova, M. (2010). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 16(24), 2978–2990. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.2978

Diagnosis

Diagnosis Who Is at Risk for SIBO or IMO?

Who Is at Risk for SIBO or IMO?