Third in a series of articles on COVID-19 and its effects on the gut, this article will explore “Long COVID” (also called “post-acute COVID syndrome”) and the role mast cells play in producing gut symptoms in individuals who have been infected with COVID-19.

As is now increasingly well known, Long COVID (LC) includes a wide array of symptoms and deficits and has been found in anywhere from 5-50% of individuals after recovering from COVID-19.1 LC affects many body systems, including (but not limited to) respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, and gastrointestinal.1 While there is no universally accepted definition of LC, it’s generally defined as signs and symptoms that are present for 4 or more weeks following SARS-CoV-2 infection.2

- What Are Mast Cells & What Is Their Role In The Gut?

- The Involvement Of Mast Cells In Acute COVID-19 Infection & Beyond

- Links Between Over-Active Mast Cells, Histamine & Food

- A Low Histamine Diet: Myriad Challenges

- If You Suspect COVID-19 Related HIT, What Can You Do?

- Learn More About Histamine Intolerance & A Low Histamine Diet

You might be interested in our other COVID articles, as well:

- IBS & The Coronavirus

- COVID-19 & Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): What Is The Connection?

- COVID-19 Vaccinations: Considerations for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

What Are Mast Cells & What Is Their Role In The Gut?

Mast cells are immune cells, specifically white blood cells, located throughout our bodies. The largest number of mast cells tend to be found where our bodies meet or are exposed to the environment, such as skin, lungs, and intestinal or genital tracts. They play a significant role in the immune system, setting off an inflammatory reaction when a “foreign invader,” such as bacteria or viruses is detected, to protect the body from infection. They also play a role in wound healing, bone growth and forming new blood vessels.3

Mast Cells Can Reside in The GI Tract

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract contains the largest population of mast cells in the body. These mast cells (MCs) help regulate what substances are allowed to cross the gut’s epithelial border and enter the bloodstream. They also play an important role in gut mucosal immunity by reacting to a variety of stimuli in our body, such as microbial, neural, immune, hormonal, metabolic or chemical triggers.4 They can also be activated by substances such as medications, infections, and insect or reptile venoms.5 Essentially, MCs serve as vigilant protectors, awaiting the signal from other areas of the body to act and defend our health.

MCs play a prominent role in what’s termed as immunoglobulin(Ig)-mediated allergic inflammation, and the symptoms we might expect from exposure to an allergen. They are also involved in a variety of other GI issues, such as gastrointestinal inflammation, functional gastrointestinal disorders, and gut infections. They may even be linked to certain neuropsychiatric conditions such as depression or anxiety, due to their impacts on the gut-brain axis.4

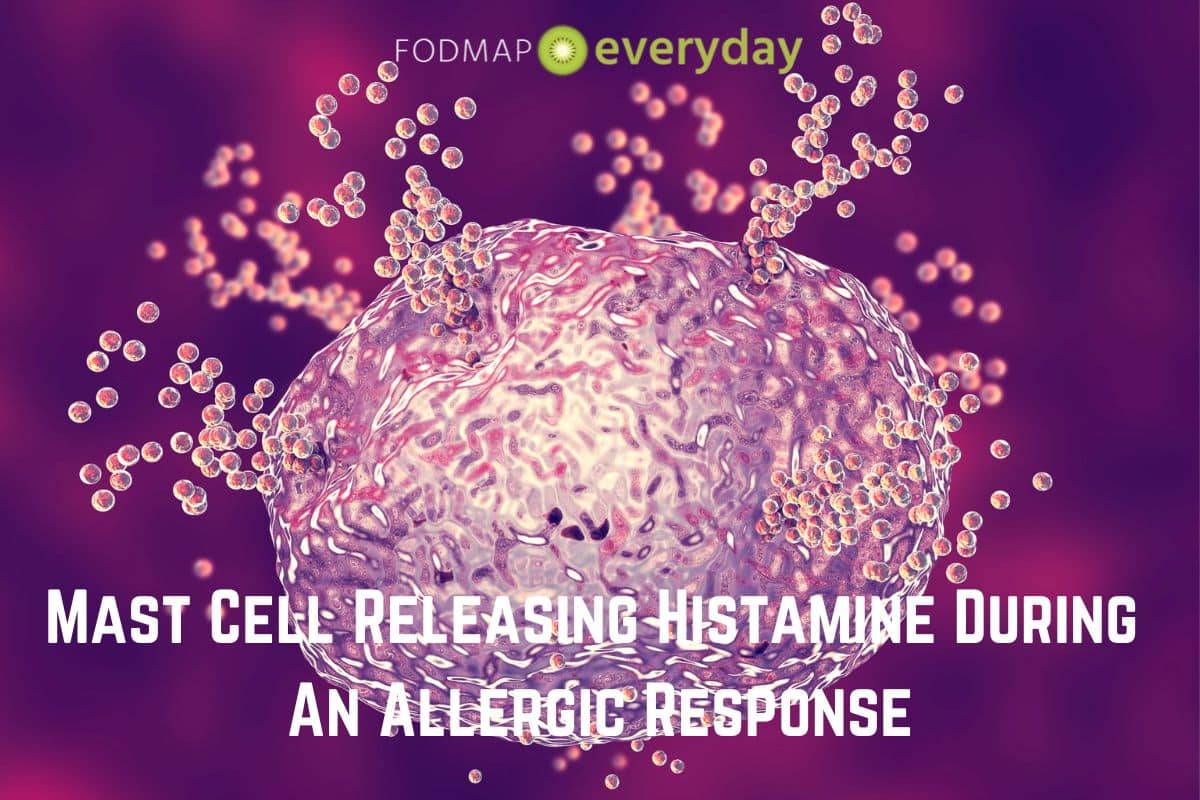

When mast cells are activated by the presence of a suspected pathogen or allergen, they release or set about in producing certain chemical mediators (stored in granules), initiating or amplifying a cascade of inflammatory reactions designed to protect the body. This chemical release is called degranulation, and these mediators may include histamine, proteases, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, heparin, and a variety of cytokines.6, 7

In the GI tract, this degranulation can lead to the enteric nervous system (the nervous system located in our gut) responding with increased gut motility, fluid secretion, smooth muscle contraction, peristalsis, visceral hypersensitivity, vomiting and/or diarrhea.7 Generally, these responses are temporary and will resolve once the immediate threat has been dealt with by the immune system.

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome

However, there are situations where these mast cell responses are overly aggressive or act upon inappropriate triggers. Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS) is a condition where mast cells may be hyper-active and/or mistakenly release too many mediators, and this causes the affected individual to experience repeated and often severe allergic symptoms. These symptoms may affect the skin, GI tract, heart, respiratory, and nervous systems.5, 8

Gut-specific symptoms typically include abdominal pain, nausea, cramping and diarrhea, and symptoms throughout the rest of the body can include flushing, itching, wheezing, coughing, lightheadedness and rapid pulse, and low blood pressure.8 And, as researchers are finding, these are many of the same symptoms found in individuals suffering from Long COVID.

The Involvement Of Mast Cells In Acute COVID-19 Infection & Beyond

As discussed in the first article of this series, GI symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, and abdominal pain may be present in anywhere from 12-20% of individuals infected with COVID. This is thought to be the result of the virus directly interacting with ACE2 receptors found throughout the gut. There is also a pathway between the gut and the lungs (the gut-lung axis) where it’s hypothesized that endotoxins, metabolites of microflora, cytokines and hormones from the gut can reach the lungs in a bi-directional (two-way) manner. This connection is illustrated in studies that have shown an increased susceptibility to respiratory diseases in patients with pre-existing or chronic GI disorders.2

In the situation of COVID-19, the SARS-CoV-2 virus can infect immune cells and epithelial cells in the lungs. The resulting hyper- or over-reaction of these cells leads to immune damage and subsequent “cytokine storm” (which can then ravage multiple organ systems in the body). These high levels of cytokines may alter the gut microbiome and lead to increased intestinal permeability and damage.2 It’s thus hypothesized that mast cells may be a significant link between the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the development of Long COVID, whereby COVID-19’s hyperinflammatory state may be mediated or brought about by mast cell activation (MCA).

And, as also mentioned in the first article in this series COVID-19 & Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): What Is The Connection? antibiotics and corticosteroids utilized by some patients during COVID-19 infection may also have an adverse effect on the gut microbiome, creating a cumulative dysbiosis, or unbalanced state, and leading to uncomfortable and lasting symptoms.

Links Between Over-Active Mast Cells, Histamine & Food

Symptoms caused by overly exuberant mast cell activation due to COVID-19 can appear in a variety of configurations, including mostly gut-focused discomfort, such as pain, cramping, nausea, and diarrhea. Or gut symptoms may also be combined with headache, skin rash, itching or flushing, dizziness, hypotension, tachycardia, and coughing or runny nose: symptoms we tend to associate more with an allergic reaction than a functional gut disorder like IBS. It’s thought that histamine, released in excessive quantities by mast cells, may be the main culprit in activating these symptoms.

Histamine Reactions Are Complex

In addition to being an inflammatory substance produced by activated mast cells, histamine also occurs naturally in some foods. Examples of foods rich in histamines include alcohol, fish and shellfish, wine, aged cheese, sausage and other processed or age meats, vinegar, chocolate, and fermented foods, such as yogurt, kefir, or sauerkraut. Histamines tend to naturally increase in concentration as food ages or is stored in the refrigerator. Depending on the cooking or food storage method, histamine content can be increased or decreased in certain foods.10

In general, most people can tolerate the amount of histamines found in an average diet, however some individuals may be especially affected by histamines found in foods. Depending on the person, histamine-induced symptoms may occur a few hours to a few days after eating foods rich in histamines, and it’s also thought that individual reactions may be “dose dependent.” This means that a small amount or occasional intake of high histamine foods may not cause issues, but large quantities or regular (i.e., cumulative) intake may indeed lead to significant symptoms over time. It also means that individual levels of tolerance can vary widely.

While research in this area is still somewhat limited, it’s theorized that symptoms resulting from eating foods rich in histamines may be due to reduced activity of an enzyme called diamine oxidase (DAO). If there isn’t enough DAO to degrade or breakdown the excess histamine, it can build up in the body, leading to symptoms.11

Other theories behind “histamine intolerance” (HIT) include genetic links, effects of other gastrointestinal or inflammatory disorders, and gut dysbiosis.12 Now, with excessive mast cell activation and histamine production linked to COVID-19 infection, we see another possible theory for HIT, especially for those individuals who may not have experienced symptoms before having COVID-19.

Given the relatively high histamine content of certain foods, dietary strategies intended to reduce intake have been proposed to help reduce some symptoms of Long COVID. Let’s explore this in more detail.

A Low Histamine Diet: Myriad Challenges

There are a number of challenges to following a low histamine diet, beginning with the fact that there is currently no “one” low histamine diet (LHD). This is due to the somewhat nascent study of MCAS and HIT, as well as wide variations in how foods are tested and when they are tested for histamine content.

Some foods naturally contain certain levels of histamines, while others may develop increased concentrations of histamines as they are processed, stored, or aged. Thus, at any point in time, the same food item can contain a different level of histamine. As you’ll see in the box that accompanies this article, there are myriad lists of the histamine content of food, and many do not “agree.” This can make it confusing and complicating to determine what to eat.

The other significant issue in following an LHD is, regardless of what food list is utilized, a large number of foods must be limited, leading to risk of nutritional deficiencies, inadequate food choice, and heightened anxiety around food and eating (the latter of which also can lead to increased symptoms, fueling a vicious cycle).

Finally, the protocols around an LHD, in terms of elimination timing and reintroduction of histamine-rich foods, are also highly variable. There is no one template for how long to omit foods and when or how much to reintroduce. It is true that the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPAH) in Sydney, Australia has a very detailed protocol for Food Chemical Intolerances, however this protocol also eliminates a wide range of other substances and foods in addition to histamines and should only be used in conjunction with an expert RPAH-trained dietitian.

If You Suspect COVID-19 Related HIT, What Can You Do?

If you feel that you have possible symptoms of MCAS or HIT after being infected with COVID-19, please don’t self-diagnose or eliminate foods from your diet. Contact your gastroenterologist or expert GI dietitian to discuss assessment and next steps.

The ideal approach is personalized and considers your health history, symptoms and current diet and food preparation regimens. Treatment strategies may include changes to food selection, storage, and cooking techniques and/or the addition of dietary enzymes, supplements and/or certain medications.

Learn More About Histamine Intolerance & A Low Histamine Diet

As mentioned in this article, the study of histamine intolerance, especially as related to COVID-19 is somewhat limited. Much of the research is anecdotal or does not meet the most rigorous scientific standards of random controlled trials (RCTs) or systematic review of multiple RCTs.

The resources below are meant only for informational purposes, and do not serve as a substitute for personalized consultation with your doctor, gastroenterologist, or dietitian.

- Dr Janice Joneja

- Joanna Baker APD

- Kate Scarlata RD

- Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Allergy Unit (RPAH)

- Swiss Interest Group Histamine Intolerance (SIGHI)

- Wendy Busse RD

- Friendly Food Recipe Book

- Allison Vickery FDN

You May Want To Read: COVID-19 and IBS Series of Articles

A series of articles on COVID-19 and its effects on the gut, with a focus on Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

References

- “How Common Is Long COVID? Why Studies Give Different Answers.” Nature.Com, 2022, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01702-2.

- Golla R, Vuyyuru SK, Kante B, et al. Disorders of gut-brain interaction in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome.Postgraduate Medical Journal Published Online First: 01 July 2022. doi: 10.1136/pmj-2022-141749

- “Mastocytosis & Mast Cells: Symptoms & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 2022, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/5908-mastocytosis. Accessed 26 September 2022.

- Albert-Bayo, Mercé et al. “Intestinal Mucosal Mast Cells: Key Modulators of Barrier Function and Homeostasis”. Cells, vol 8, no. 2, 2019, p. 135. MDPI AG, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8020135. Accessed 26 Sept 2022.

- “Mast Cell Activation Syndrome.” American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology.https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-treatments/related-conditions/mcas#:~:text=In%20allergic%20reactions%2C%20this%20release,these%20mediators%20is%20called%20degranulation. Accessed 26 September 2022

- Castellis, M MD, PhD and Bankova, L MD. “Mast Cell-Derived Mediators.” Up to Date. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/mast-cell-derived-mediators#:~:text=Mast%20cell%20secretory%20granules%20contain,alpha%20(TNF%2Dalpha). Updated 26 May 2022. Accessed 26 September 2022.

- Krystel-Whittemore, Melissa et al. “Mast Cell: A Multi-Functional Master Cell”. Frontiers In Immunology, vol 6, 2016. Frontiers Media SA, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00620. Accessed 26 Sept 2022.

- “Mast Cell Activation Syndrome.” National Institutes of Health, 2022, https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/12981/mast-cell-activation-syndrome. Last updated 8 November 2021. Accessed 26 September 2022.

- Weinstock, Leonard B. et al. “Mast Cell Activation Symptoms Are Prevalent In Long-COVID”. International Journal Of Infectious Diseases, vol 112, 2021, pp. 217-226. Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.043. Accessed 26 Sept 2022.

- Chung, Bo Young et al. “Effect Of Different Cooking Methods On Histamine Levels In Selected Foods”. Annals Of Dermatology, vol 29, no. 6, 2017, p. 706. Korean Dermatological Association And The Korean Society For Investigative Dermatology, https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2017.29.6.706. Accessed 26 Sept 2022.

- “Caution advised with low histamine diets for Long Covid.” British Dietetics Association. 20 May 2021. https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/caution-advised-with-low-histamine-diets-for-long-covid.html. Accessed 26 September 2022.

- Zhao, Ying et al. “Histamine Intolerance—A Kind Of Pseudoallergic Reaction”. Biomolecules, vol 12, no. 3, 2022, p. 454. MDPI AG, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12030454. Accessed 9 Oct 2022.