*But Are Too Afraid to Ask

Whether you refer to it as being flatulent, farting, tooting or breaking wind, passing intestinal gas is something common to all human beings. Everyone does it every single day to varying degrees.

But despite the fact that passing gas is one of the most normal, mundane things we humans do, it’s often the source of many disquieting emotions: from embarrassment when we have to do it around others, to anxiety about what its frequency or character might mean about our health, to deep distress when it is accompanied by uncomfortable feelings of pressure or pain.

Why Do We Fart?

People fart to release gasses that are either generated in our bowels by the resident gut microbiota (the ecosystem of microorganisms—mostly bacteria—that inhabit our digestive tract) or that are swallowed in the form of air during the course of our usual eating, drinking, gulping, slurping, sniffling, gum chewing, talking, snoring or smoking activities.

Available research suggests that the average person expels between a half liter to two liters of gas per day through farting, delivered via about 10 to 20 farts per day.

Foods that feed the microbiota better—namely, carbohydrate foods in general, and higher fiber carbohydrates in particular—are most likely to result in intestinal gas production. This is because most bacterial residents we host are programmed to ferment carbohydrates, and fiber is the category of carbohydrate they are most likely to encounter in our colons, where the majority of them live. After all, fiber—by definition—is indigestible to humans.

The Role Of Fiber In Our Farts

Among fiber containing foods, however, certain ones are more readily fermentable by gut bacteria than others, and therefore are more likely to result in greater gas production than those containing less fermentable types of fiber.

These more fermentable forms of fiber are also known as “high FODMAP” foods, which explains why low FODMAP diets are often employed to help manage problematic gas and bloating issues.

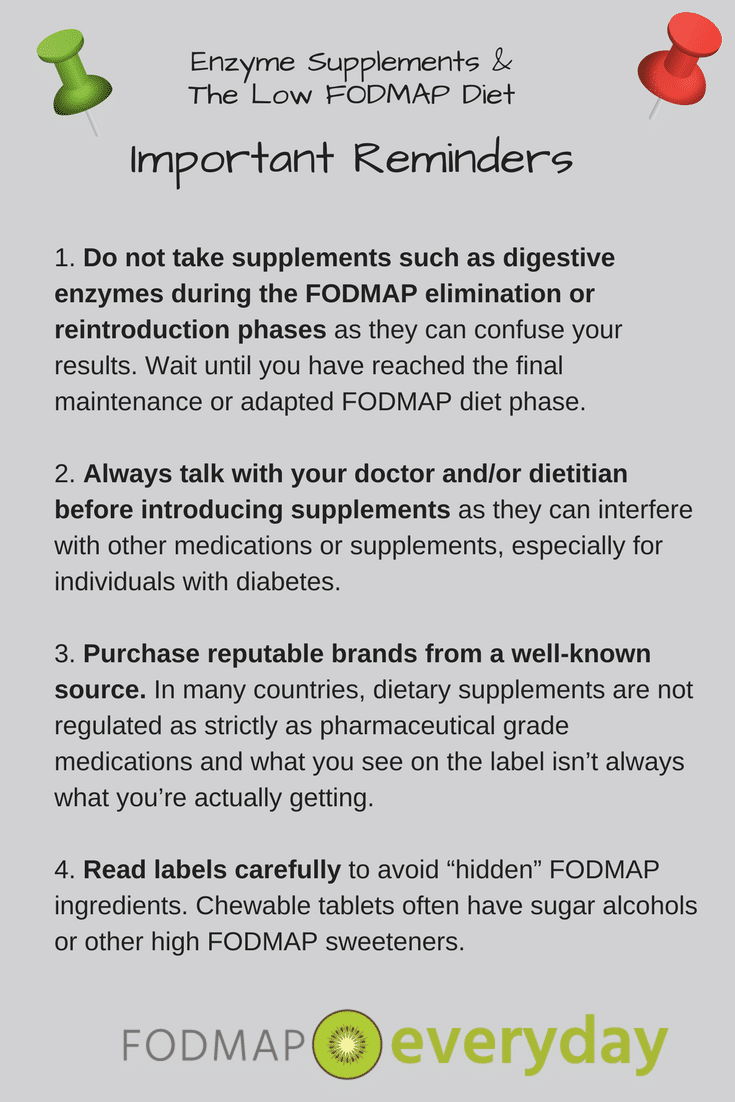

Specific digestive enzyme supplements that break down certain dietary fibers that humans lack the ability to digest—like alpha galactosidase, marketed as Beano and under other names—have been shown to help people fart less following consumption of (high FODMAP foods like) beans compared to placebo. In other words, by making undigestible fibers digestible, there is less fermentable residue leftover for the gut bacteria to ferment… and therefore, less farting.

Typically, it takes between 4 to 8 hours from a food we eat to reach the colon and start being fermented, which means if you start farting a little while after lunch, you’d generally need to look back to see what you ate at breakfast to help suss out the culprit. (The timing of farting onset after intake may be closer to two hours if you are completely fasted or just drinking a liquid, and it may be closer to one hour if you are overgrowing bacteria in your small intestine as is the case when you have a condition called SIBO.)

You may want to read: Fiber and IBS: What You Need To Know

Looking to share this information with your clients or a loved one? Download this article as an ebook for 99 cents.

Why Vegans Fart So Much

High fiber, plant-rich diets are typically associated with more frequent farting (and presumably greater amounts of gas) compared to lower fiber diets; indeed, many people who adopt very low carb or keto-style diets often remark at how much less gas they find themselves passing on their new diet.

But having larger amounts of intestinal gas does not necessarily signal something is amiss with your health; in fact, to a large degree, farting is often the byproduct of a healthy diet full of whole grains, beans, fruits, veggies, nuts and seeds (no good deed goes unpunished, right?)

My vegan patients consume some of the most nutrient rich diets I’ve seen—and can also be some of the gassiest people I know. They’ll probably live for years longer than the rest of us will, leaving a cloud of flatulence in their wake as they toast their long lives over kale smoothies.

You may want to read our Vegan and Low FODMAP Series articles.

Everyone’s Farts Are Unique

When gas is primarily generated by dietary choices rather than swallowed air, there can be substantial person-to-person variation in the amount of farting that results from a given food or set of foods.

This variation appears related to the particular mix of microbes an individual harbors inside—the unique composition of his or her gut microbiota—which seems to contribute to differences in sensitivity to the presence of gas that impacts how often our bodies are triggered to release it by farting as much as it does differences in the amount of gas we actually produce from the foods we eat.

Just How Gassy Are You?

One (fascinating) study published in the journal Gut that examined the effect of increased intake of fiber between people who complained of excessive farting and a set of controls without digestive complaints found that the fartier people were more likely to harbor an abundant level of three specific bacterial taxa (classifications) compared to the control group.

Furthermore, in response to adopting a higher fiber diet that also increased intake of higher FODMAP foods like whole wheat, beans, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, onions, garlic, artichokes, prunes and figs, the ‘gassier’ group of participants experienced a more significant change in the composition of their gut microbes compared to the control group, whose gut microbiota also changed in response to the diet, but to a significantly lower degree.

Sensitivity To Gas Varies

However, it is not clear that people who farted more often in this study actually produced more gas than the people who farted less often. Researchers measured the amount of gas expelled by participants from both groups for 6 hours following standardized test meals.

Despite both groups producing an almost identical amount of gas in response to the meals, participants who had longstanding complaints of excessive farting did indeed fart significantly more times compared to the controls.

The researchers hypothesized that this could be due to differences in sensitivity to gas within the rectum and/or functioning of the anal sphincter muscle that resulted in more frequent urges to release (smaller amounts) of gas in the fartier group versus less frequent urges to fart (larger amounts) of gas in the control group.

Hypersensitivity Exists

With this in mind, the researchers wondered whether the observed differences in the gut microbiota might actually be responsible for the gut’s hypersensitivity to gas more so than differences in actual gas volume production.

Farting Is Only A Problem If It’s A Problem

So, we’ve established that farting is a normal part of being human, and that people who eat the types of diverse, high fiber diets that are associated with longevity and lower risk of chronic disease are also likely to experience an uptick in the amount of intestinal gas they produce. In other words, farting is not inherently problematic.

However, for some people, even the presence of ‘normal’ amounts of intestinal gas can be extremely problematic from a quality-of-life perspective.

As the Gut study referenced above suggests, there seems to be significant variation among people around sensitivity to the presence of gas in our digestive tracts, and this both influences how frequently we might fart (even when we have the same amounts of intestinal gas) as well as how much distress and discomfort we feel in response to a given amount of gas. For people in this camp, something as common, normal and medically benign as farting can indeed be quite problematic.

IBS & Farting

The term we use to describe intense, higher-than-average degrees of sensation to stimuli in the digestive tract is called “visceral hypersensitivity,” and this is a hallmark characteristic of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

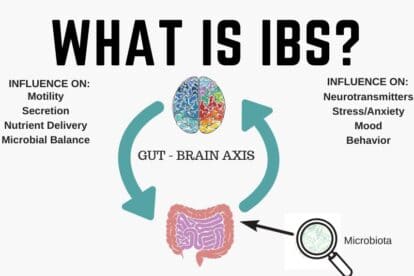

IBS is one of many so-called disorders of the gut-brain interaction (DGBIs) in which the two-way communication channel between the brain and the digestive tract isn’t functioning properly.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) sufferers know all too well the realities of the gut-brain connection: uncomfortable or embarrassing gut symptoms cause stress, which then trigger further painful symptoms.

Misinterpreted messages related to the motor or sensory functions of the gut result in irregular motility patterns and a lower threshold for pain relative to stimuli within the gut—like the presence of gas, stool or spices—compared to healthy controls.

In addition to visceral hypersensitivity, another reason some people may experience increased feelings of bloating and discomfort from intestinal gas may have to do with how gas is distributed throughout their intestinal tract.

Spanish researcher Juan Malagelada, MD and his colleagues published a paper in 2017 in which they shared previously their published images of CT scans of a patient who complained frequently of “bloating”—both when the patient was minimally symptomatic and when the patient was more symptomatic.

Comparing these two imaging studies, the authors noted that the amount of intestinal gas present differed by a miniscule amount—only 22 ml—but that the way the gas was distributed throughout the digestive tract was very different.

Gas Can Build Up

During an acute bloating episode, the patient’s intestinal gas was “pooled” more into more concentrated regions, compared to being more evenly distributed throughout the intestine when the patient was less visibly distended and less subjectively distressed.

They explain how disturbances in intestinal motility—such as those characteristic of IBS—may result in such ‘gas pooling’ effects that result in both feelings of excessive discomfort as well as objectively visible abdominal distension even when the actual amount of intestinal gas is not necessarily elevated.

When someone has IBS, and gas is indeed problematic, it often becomes necessary to undertake interventions that reduce the amount of intestinal gas (some form of FODMAP elimination typically); reduce the likelihood of gas pooling (usually through medications that regulate intestinal motility); and/or reduce the overreactive pain response to the presence of even ‘normal’ amounts of gas (typically through antidepressant medications, neuromodulating medications, or GI psychology interventions like gut-directed hypnotherapy).

Why Do Farts Smell?

Even among people whose farting does not cause physical pain or distress, the odor of your gas may be something that creates mental anguish. Over the years, more than one patient has come to me for dietary advice aimed at manipulating the odor of their farts. (For the record: I do not know how to fashion designer farts on demand, so please don’t ask.)

Various sulfur-containing gases in the GI tract are responsible for most of the odor of our farts, and our dietary choices can play a role in how much of these gases we make. (Other gases we pass are not odorous; these include nitrogen, hydrogen, methane and carbon dioxide.)

Among these sulfur containing gases, hydrogen sulfide can often smell (rotten) egg-like when passed, whereas dimethyl sulfide is most often described as ‘cabbage-like.’ Methanethiol is described in the research literature as having a “strong and disagreeable odor” that we associate with barnyards, feces, composting and landfills.

The cocktail of these three gases in their relative amounts will confer upon your farts most of their signature smell, and the relative balance of these gases will vary based on your dietary choices and the unique composition of your gut microbiome.

Fart Fragrance

Higher intake of foods that contain sulfur may result in a greater amount of malodorous gas, though sulfur is present in such a wide variety of healthy foods that it’s really not appropriate (or realistic) to eliminate them all in the service of micromanaging the scent of your farts.

Foods that contain sulfur include meat, poultry, eggs, beans/lentils/legumes, nuts, seeds, onions, garlic and all the veggies in the cruciferous family—like cabbage, Brussels sprouts, kale and broccoli. Of note, many popular dietary supplements contain sulfur compounds and could also impact the scent of your farts; these include glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, MSM (methylsulfonylmethane) and B-complex products.

When Might Farting Indicate That Something Is Amiss?

Trace amounts of other non-sulfur gases called volatile organic compounds (or, VOCs) also play a role in the scenting our farts, and these often account for why our farts smell different—and often particularly toxic—when we are sick.

It is widely recognized in the healthcare community that nurses are particularly adept at predicting whether a patient has a bacterial infection caused by the bacteria Clostridium difficile (so-called “C. diff”) due to the unmistakably strong, signature smell of their gas and stool.

And many dog owners know that when their dog’s farts start to stink out of the blue, it can be a sign of infection with an intestinal parasite called giardia. Interestingly, some researchers are investigating ways to use electronic sensors paired with artificial intelligence toward analyzing the chemical composition of various human outputs to help diagnose diseases.

A 2016 paper published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology described the state of research into using these so-called “electronic noses” for the purpose of analyzing all manner of body odors, from breath and urine to “fecal headspace”—the gases emitted by a poop—to accurately identify people with colon cancer, various types of infectious diarrhea, Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and celiac disease compared to healthy controls.

Anecdotally, I’ve had many patients with newly diagnosed celiac disease describe to me that one of the concerning symptoms that led them to seek medical care was an uptick in unusually foul-smelling farts that were noticeably different than their typical.

In other words, if you have a sudden and marked change in the smell of your flatus despite no significant change in your diet, it’s not a terrible idea to get things checked out, particularly if it is accompanied by a change in your stool quality or regularity, whether in the form of diarrhea or constipation.

The Takeaway

Everybody farts, and everybody’s farts smell to some degree. Manipulating your diet and supplement regimen can produce some change in the amount of gas you pass and even the smell of that gas to some extent, but often these dietary changes represent a real tradeoff in the form of eliminating nutrient-rich, health promoting foods.

Some such dietary interventions include reduced intake of high FODMAP foods toward reducing the total amount of gas you produce, to reducing certain types of high-sulfur foods to mitigate the strong odor of your farts.

Of note, charcoal filters do a commendable job neutralizing smell of farts, and charcoal liners for underwear are available; they may be particularly handy in situations in which farting is not socially expedient (airplanes come to mind).

Some people—particularly those with IBS—may fart more frequently or experience more bloating and discomfort associated with their intestinal gas, even if they do not necessarily have more total gas the person sitting in the next cubicle over. There are a variety of dietary, behavioral and pharmacological remedies that can be combined to better control these symptoms.

If this article has helped you come to terms with the mundane, benign nature of your farting– its frequency, its odor or just the very necessity of its existence–then this may be the last 2300 words you ever need to read about flatulence. But if your farting is a source of physical discomfort, a serious social liability or a seeming harbinger of something different at large inside your intestines, then don’t be too shy about making an appointment with a GI dietitian or a gastroenterologist to discuss your concerns. There’s no sound or scent that your intestines produce that we haven’t encountered before, and chances are high that something can be done to mitigate the problem.

Read All Of Tamara’s Articles:

- What Conventional Wisdom Gets Wrong About Bloating

- Timing of Digestive Symptoms: What It Means

- What Is Leaky Gut Syndrome?

- Are You Full of Sh*t? Stool Burden and the Low FODMAP Diet

- Everything You Want to Know About Farting*

- 5 Reasons to Skip Gut Microbiome Testing – For Now

- Exclusive Interview with Dietitian Tamara Duker Freuman

- Q & A With The Author Of “Regular, The Ultimate Guide to Taming Unruly Bowels and Achieving Inner Peace”